Piracetam

Piracetam is a drug marketed as a treatment for myoclonus[3] and a cognitive enhancer.[4] Evidence to support its use is unclear, with some studies showing modest benefits in specific populations and others showing minimal or no benefit.[5][6] Piracetam is sold as a medication in many European countries. In the United States, piracetam is sold as a dietary supplement, despite being prohibited by the FDA.[4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Breinox, Dinagen, Lucetam, Nootropil, Nootropyl, Oikamid, Piracetam and many others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, parenteral, or vaporized |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100% |

| Onset of action | Swiftly following administration. Food delays time to peak concentration by 1.5 hrs approximately to 2-3 hrs since dosing.[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 4–5 hr |

| Excretion | Urinary |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.466 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H10N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 142.158 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 152 °C (306 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

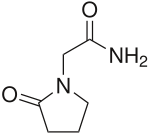

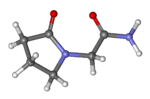

Piracetam is in the racetams group, with chemical name 2-oxo-1-pyrrolidine acetamide. It is a derivative of the neurotransmitter GABA[5] and shares the same 2-oxo-pyrrolidone base structure with pyroglutamic acid. Piracetam is a cyclic derivative of GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid). Related drugs include the anticonvulsants levetiracetam and brivaracetam, and the putative nootropics aniracetam and phenylpiracetam.

Efficacy

Dementia

A 2001 Cochrane review concluded that there was not enough evidence to support piracetam for dementia or cognitive problems.[6] A 2005 review found some evidence of benefit in older subjects with cognitive impairment.[5] In 2008, a working group of the British Academy of Medical Sciences noted that many of the trials of piracetam for dementia were flawed.[7]

There is no good evidence that piracetam is of benefit in treating vascular dementia.[8]

Depression and anxiety

Some sources suggest that piracetam's overall effect on lowering depression and anxiety is higher than on improving memory.[9] However, depression is reported to be an occasional adverse effect of piracetam.[10]

Other

Piracetam may facilitate the deformability of erythrocytes in capillary which is useful for cardiovascular disease.[5][3]

Peripheral vascular effects of piracetam have suggested its use potential for vertigo, dyslexia, Raynaud's phenomenon and sickle cell anemia.[5][3] There is no evidence to support piracetam's use in sickle cell crisis prevention[11] or for fetal distress during childbirth.[12] There is no evidence for benefit of piracetam with acute ischemic stroke,[13] though there is debate as to its utility during stroke rehabilitation.[14][15]

Side effects

Piracetam has been found to have very few side effects, and those it has are typically "few, mild, and transient."[16] A large-scale, 12-week trial of high-dose piracetam found no adverse effects occurred in the group taking piracetam as compared to the placebo group.[17] Many other studies have likewise found piracetam to be well tolerated.[16][18][19]

Symptoms of general excitability, including anxiety, insomnia, irritability, headache, agitation, nervousness, tremor, and hyperkinesia, are occasionally reported.[10][20][21] Other reported side effects include somnolence, weight gain, clinical depression, weakness, increased libido, and hypersexuality.[10]

According to a 2005 review, piracetam has been observed to have the following side effects: hyperkinesia, weight gain, nervousness, somnolence, depression and asthenia.[5]

Piracetam reduces platelet aggregation as well as fibrinogen concentration, and thus is contraindicated to patients suffering from cerebral hemorrhage.[5][3]

Toxicity

Piracetam does not appear to be acutely toxic at the doses used in human studies.[6][16][18]

The LD50 for oral consumption in humans has not been determined.[22] The LD50 is 5.6 g/kg for rats and 20 g/kg for mice, indicating extremely low acute toxicity.[23] For comparison, in rats the LD50 of vitamin C is 12 g/kg and the LD50 of table salt is 3 g/kg.

Mechanisms of action

Piracetam's mechanism of action, as with racetams in general, is not fully understood. The drug influences neuronal and vascular functions and influences cognitive function without acting as a sedative or stimulant.[5] Piracetam is a positive allosteric modulator of the AMPA receptor, although this action is very weak and its clinical effects may not necessarily be mediated by this action.[24] It is hypothesized to act on ion channels or ion carriers, thus leading to increased neuron excitability.[22] GABA brain metabolism and GABA receptors are not affected by piracetam[25]

Piracetam improves the function of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine via muscarinic cholinergic (ACh) receptors, which are implicated in memory processes.[26] Furthermore, piracetam may have an effect on NMDA glutamate receptors, which are involved with learning and memory processes. Piracetam is thought to increase cell membrane permeability.[26][27] Piracetam may exert its global effect on brain neurotransmission via modulation of ion channels (i.e., Na+, K+).[22] It has been found to increase oxygen consumption in the brain, apparently in connection to ATP metabolism, and increases the activity of adenylate kinase in rat brains.[28][29] Piracetam, while in the brain, appears to increase the synthesis of cytochrome b5,[30] which is a part of the electron transport mechanism in mitochondria. But in the brain, it also increases the permeability of some intermediates of the Krebs cycle through the mitochondrial outer membrane.[28]

History

Piracetam was first made some time between the 1950s and 1964 by Corneliu E. Giurgea.[31] There are reports of it being used for epilepsy in the 1950s.[32]

Society and culture

In 2009 piracetam was reportedly popular as a cognitive enhancement drug among students.[33]

Legal status

Piracetam is an uncontrolled substance in the United States meaning it is legal to possess without a license or prescription.[34]

Regulatory status

In the United States, piracetam is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration.[1] Piracetam is not permitted in compounded drugs or dietary supplements in the United States.[35] Nevertheless, it is available in a number of dietary supplements.[4]

In the United Kingdom, piracetam is approved as a prescription drug Prescription Only Medicine (POM) number is PL 20636/2524[36] for adult with myoclonus of cortical origin, irrespective of cause, and should be used in combination with other anti-myoclonic therapies.[37]

In Japan piracetam is approved as a prescription drug.[38]

Piracetam has no DIN in Canada, and thus cannot be sold but can be imported for personal use in Canada.[39]

See also

- AMPA receptor positive allosteric modulator

- Aniracetam

- Brivaracetam — an analogue of piracetam with the same additional side chain as levetiracetam and a three–carbon chain. It exhibits greater antiepileptic properties than levetiracetam in animal models, but with a somewhat smaller, although still high, therapeutic range.

- Hydergine

- Levetiracetam — an analogue of piracetam bearing an additional CH3–CH2– sidechain and bearing antiepileptic pharmacological properties through a poorly understood mechanism probably related to its affinity for the vesicle protein SV2A.

- Oxiracetam

- Phenylpiracetam — a phenylated analog of the drug piracetam which was developed in 1983 in Russia where it is available as a prescription drug.

- Pramiracetam

References

- "Piracetam". DrugBank database.

- Leaflet of Piracetam

- "Nootropil Tablets 1200 mg". (emc). 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- Cohen, Pieter A.; Zakharevich, Igor; Gerona, Roy (25 November 2019). "Presence of Piracetam in Cognitive Enhancement Dietary Supplements". JAMA Internal Medicine. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5507. PMC 6902196. PMID 31764936.

- Winblad B (2005). "Piracetam: a review of pharmacological properties and clinical uses". CNS Drug Reviews. 11 (2): 169–82. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00268.x. PMC 6741724. PMID 16007238.

- Flicker, L; Grimley Evans, G (2001). "Piracetam for dementia or cognitive impairment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001011. PMID 11405971.

- Horne G, et al. (May 2008). Brain science, addiction and drugs (PDF) (Report). Academy of Medical Sciences. p. 145. ISBN 1-903401-18-6.

- Farooq MU, Min J, Goshgarian C, Gorelick PB (September 2017). "Pharmacotherapy for Vascular Cognitive Impairment". CNS Drugs (Review). 31 (9): 759–776. doi:10.1007/s40263-017-0459-3. PMID 28786085.

Other medications have been considered or tried for the treatment of VCI or VaD. These include [...] piracetam. There is no convincing evidence about the efficacy of these medications in the treatment of VCI.

- Malykh AG, Sadaie MR (February 2010). "Piracetam and piracetam-like drugs: from basic science to novel clinical applications to CNS disorders". Drugs. 70 (3): 287–312. doi:10.2165/11319230-000000000-00000. PMID 20166767.

- Nootropil®. Arzneimittel-Kompendium der Schweiz. 2013-09-12. Retrieved 2013-10-27.

- Al Hajeri A, Fedorowicz Z (February 2016). "Piracetam for reducing the incidence of painful sickle cell disease crises". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD006111. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006111.pub3. PMID 26869149.

- Hofmeyr, GJ; Kulier, R (13 June 2012). "Piracetam for fetal distress in labour". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD001064. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001064.pub2. PMC 7048034. PMID 22696322.

- Ricci S, Celani MG, Cantisani TA, Righetti E (September 2012). "Piracetam for acute ischaemic stroke". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD000419. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000419.pub3. PMC 7034527. PMID 22972044.

- Zhang J, Wei R, Chen Z, Luo B (July 2016). "Piracetam for Aphasia in Post-stroke Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". CNS Drugs. 30 (7): 575–87. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0348-1. PMID 27236454.

- Yeo SH, Lim ZI, Mao J, Yau WP (October 2017). "Effects of Central Nervous System Drugs on Recovery After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Clinical Drug Investigation. 37 (10): 901–928. doi:10.1007/s40261-017-0558-4. PMID 28756557.

- Koskiniemi M, Van Vleymen B, Hakamies L, Lamusuo S, Taalas J (March 1998). "Piracetam relieves symptoms in progressive myoclonus epilepsy: a multicentre, randomised, double blind, crossover study comparing the efficacy and safety of three dosages of oral piracetam with placebo". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 64 (3): 344–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.64.3.344. PMC 2169975. PMID 9527146.

- De Reuck J, Van Vleymen B (March 1999). "The clinical safety of high-dose piracetam--its use in the treatment of acute stroke". Pharmacopsychiatry. 32 (Suppl 1): 33–7. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979234. PMID 10338106.

- Fedi M, Reutens D, Dubeau F, Andermann E, D'Agostino D, Andermann F (May 2001). "Long-term efficacy and safety of piracetam in the treatment of progressive myoclonus epilepsy". Archives of Neurology. 58 (5): 781–6. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.5.781. PMID 11346373.

- Giurgea C, Salama M (1977). "Nootropic drugs". Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. 1 (3–4): 235–247. doi:10.1016/0364-7722(77)90046-7.

- Chouinard G, Annable L, Ross-Chouinard A, Olivier M, Fontaine F (1983). "Piracetam in elderly psychiatric patients with mild diffuse cerebral impairment". Psychopharmacology. 81 (2): 100–6. doi:10.1007/BF00429000. PMID 6415738.

- Hakkarainen H, Hakamies L (1978). "Piracetam in the treatment of post-concussional syndrome. A double-blind study". European Neurology. 17 (1): 50–5. doi:10.1159/000114922. PMID 342247.

- Gouliaev AH, Senning A (May 1994). "Piracetam and other structurally related nootropics". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 19 (2): 180–222. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(94)90011-6. PMID 8061686.

- "Piracetam Material Safety Sheet" (PDF). Spectrum.

- Ahmed AH, Oswald RE (March 2010). "Piracetam defines a new binding site for allosteric modulators of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 53 (5): 2197–203. doi:10.1021/jm901905j. PMC 2872987. PMID 20163115.

- Giurgea CE (January 1982). "The nootropic concept and its prospective implications". Drug Development Research. 2 (5): 441–446. doi:10.1002/ddr.430020505. ISSN 1098-2299.

- Winnicka K, Tomasiak M, Bielawska A (2005). "Piracetam--an old drug with novel properties?". Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 62 (5): 405–9. PMID 16459490.

- Müller WE, Eckert GP, Eckert A (March 1999). "Piracetam: novelty in a unique mode of action". Pharmacopsychiatry. 32 (Suppl 1): 2–9. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979230. PMID 10338102.

- Grau M, Montero JL, Balasch J (1987). "Effect of Piracetam on electrocorticogram and local cerebral glucose utilization in the rat". General Pharmacology. 18 (2): 205–11. doi:10.1016/0306-3623(87)90252-7. PMID 3569848.

- Nickolson VJ, Wolthuis OL (October 1976). "Effect of the acquisition-enhancing drug piracetam on rat cerebral energy metabolism. Comparison with naftidrofuryl and methamphetamine". Biochemical Pharmacology. 25 (20): 2241–4. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(76)90004-6. PMID 985556.

- Tacconi MT, Wurtman RJ (1986). "Piracetam: physiological disposition and mechanism of action". Advances in Neurology. 43: 675–85. PMID 3946121.

- Li JJ, Corey EJ (2013). Drug Discovery: Practices, Processes, and Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons. p. 276. ISBN 9781118354469.

- Schmidt D, Shorvon S (2016). The End of Epilepsy?: A History of the Modern Era of Epilepsy Research 1860-2010. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780198725909.

- Medew J (1 October 2009). "Call for testing on 'smart drugs'". Fairfax Media. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- "Erowid Piracetam Vault: Legal Status".

- Jann Bellamy (26 September 2019). "FDA proposes ban on curcumin and other naturopathic favorites in compounded drugs". Science-Based Medicine.

- http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/spcpil/documents/spcpil/con1547788739542.pdf

- "Nootropil Tablets 800 mg". (emc).

- "UCB's piracetam approved in Japan". The Pharma Letter. 25 November 1999.

- "Guidance Document on the Import Requirements for Health Products under the Food and Drugs Act and its Regulations (GUI-0084)". Health Canada / Health Products and Food Branch Inspectorate. 1 June 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- UCB Pharma Limited (2005). "Nootropil 800 mg & 1200 mg Tablets and Solution". electronic Medicines Compendium. Datapharm Communications. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Piracetam. |

- Gouliaev AH, Senning A (May 1994). "Piracetam and other structurally related nootropics". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 19 (2): 180–222. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(94)90011-6. PMID 8061686.